Did you know that Australians eat about 50,000 tonnes of tuna every year? [1] That’s roughly the same weight as the Sydney Harbour Bridge! Unfortunately, the global tuna industry is rife with overfishing and inappropriate fishing methods that harm protected species, and it can be difficult to tell the difference between good and bad tuna on the shelf.

That’s why we’ve created our handy tuna guide below. This guide should point you towards the responsibly sourced tuna products in Australia while steering you away from accidentally supporting harmful companies and practices.

If the product isn’t labelled with the species, how it was caught, and where it was caught then you should avoid it.

THE BEST AVAILABLE:

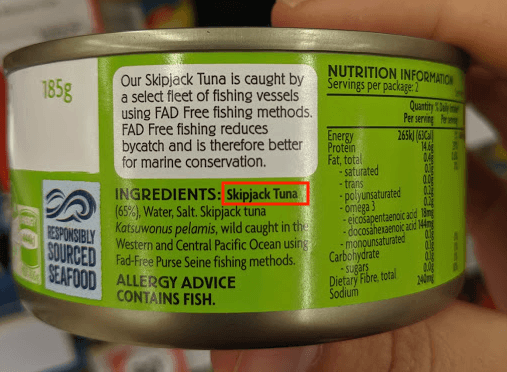

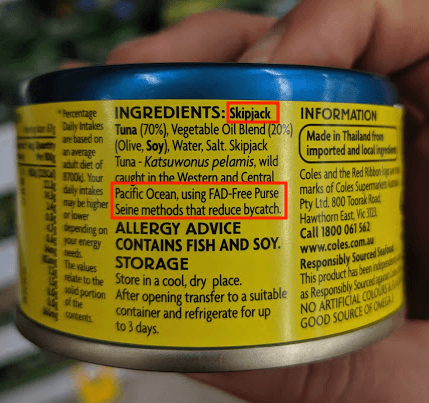

Species: Skipjack and Albacore Tuna species from the Western and Central pacific are usually better choices

Method: Pole and line, trolling or handline fishing methods, purse seine FAD-free fishing methods

AVOID:

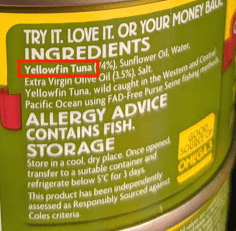

Species: Yellowfin tuna

DO NOT BUY:

Species: Bluefin and Bigeye tuna

Methods: FAD Purse seine, Gillnetting, imported longlining

NOTES:

‘Dolphin friendly’ fishing methods and labeling are not a key indicator of sustainable practices as dolphins don’t usually cohabitate with tuna and these methods tell you nothing about the main principles of sustainability.

Decoding The Tuna Can: The Fish and the Method

There are two crucial parts to a tuna can that every tuna shopper should know:

Tuna species: Whether or not the species of tuna in the can is from a population that is fished at sustainable rate

Fishing Method: Whether or not the fishing method used results in bycatch of threatened species like turtles, sharks, and juvenile tuna

If you would like to know more about selecting your canned tuna, you can read the section below for more info.

Tuna species to avoid

Tuna is a family of fish that come in many different species, some from populations that are doing better than others. It is therefore critical to ensure that the species of tuna that you buy is one that is not in harvested at a rate that is threatening the population. Make sure that the tuna product clearly identifiesthe species name, otherwise don’t buy it. If it’s labelled as “thunnus” or “genus thunnus” it simply means it is in the tuna family, not which type of species has been caught. Read on to find which species are sustainably sourced and which aren’t.

Critically Endangered

- Bluefin Tuna (Thunnus maccoyii, Thunnus orientalis & Thunnus thynnus)

Bluefin is typically the most expensive tuna and classified as an endangered species. Mostly found in high-end restaurants as sashimi or sushi, Bluefin has three species; Atlantic, Pacific and Southern. Bluefin has been extremely overfished, and Southern Bluefin, the only type caught and sold in Australia, is already classified as critically endangered. > AVOID BLUEFIN TUNA

- Bigeye tuna (Thunnus obesus)

Bigeye tuna often consumed as tuna steaks, sushi or sashimi and is one of the most expensive types of tuna, often found in restaurants. The bigeye tuna population is low with overfishing occurring in the eastern and western Pacific Ocean. > AVOID BIGEYE TUNA

Threatened tuna

- Yellowfin (Thunnus albacares)

Yellowfin mostly served as sashimi, sushi, tuna steak or canned. Yellowfin is also vulnerable to population decline through increased bycatch caused by fishing vessels using FADs, fishing levels for yellowfin tuna in Australia are probably OK, but in the Pacific and Indian Oceans they are under more pressure. > EAT LESS YELLOWFIN TUNA

- Albacore (Thunnus Alalunga)

Albacore is often sold as “white tuna” in the supermarket and is mainly canned. There is some concern in the decline population of Albacore in the Pacific Ocean in the near future due to overfishing. > EAT LESS Albacore

Less-concerned tuna

- Skipjack (Katsuwonus Pelamis)

Mainly found in the tropical areas of the Indian, Atlantic and Pacific Ocean, Skipjack is considered as the most sustainable tuna, but it can still be caught using unsustainable practices. > MOST RESPONSIBLE OPTION

Feel free to read this page if you want to learn more about how endangered these different tuna species are.

Fishing methods to avoid

Fishing methods range dramatically in terms of their effect on the environment. Some have low impact, while others are associated with overfishing and bycatch where other species are caught, killed, and thrown away.

Unacceptable

- Use of FADs with purse seine nets

FADs are rafts made from various materials, like bamboo or plastic frames covered in netting. Tuna and other marine life are attracted to these floating objects. Setting purse seine nets on FADs catches and kills 3 to 7 times more non-target species than other methods, including threatened sharks. High numbers of juvenile bigeye and yellowfin tuna are also caught. Lost and/or abandoned FADs often end up on beaches and tangled on coral reefs causing untold damage for years after last use.

- Gillnetting, Longlining

These fishing methods applied on an industrial scale can have disastrous impacts on marine ecosystems as the percentage of bycatch is very high when done without strict management. The bycatch can include sea turtles, sharks and/or dolphins. Australian longlining is managed much more stringently than overseas so has less impact.

Acceptable

- FAD-free Purse Seine

A Purse Seine is a large floating net that encircles a school of fish and then is drawn tight like a drawstring purse. It accounts for 63% of the global tuna catch and considered relatively responsible as long as it’s FAD-free. HOWEVER, a pole-and-line caught tuna is a better option. Look at the canned tuna label to verify whether or not it’s FAD-free.

Most Sustainable, least risk of bycatch

- Pole-and-line caught

The Pole-and-line fishing technique is considered to result in the lowest amount of bycatch and overfishing. This method also creates more jobs for the local fishing communities including in the Western Central Pacific – where the majority of Australian tuna comes from – as it requires more fisherman than industrial fishing. Trolling, the process of using many fishing lines behind a moving boat and handlining are similar techniques that are also sustainable.

Symbols and certifications can be misleading

Greenpeace does not endorse any third party certifiers and their labels should not be considered a guarantee of sustainability. There are several types of symbols and certifications on tuna cans however they can be misleading. The most important things are the name of the species of tuna and the fishing method, which should both be labeled on the can. If not, avoid them even if certified.

Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) Certified

MSC offers the most rigorous traceability certification on canned tuna through certifying supply chains from fishing vessels to processing plants to wholesalers and retailers.

However, there are critics arguing that it certifies unsustainable fisheries or fisheries with insufficient information on their fishing techniques and practices.

Dolphin safe labels

The label ‘dolphin friendly’ should not be used as an indicator of how sustainable the tuna is in Australia. This is because most of the tuna in our shopping centers comes from the Pacific where dolphins do not congregate near tuna. It is possible that a dolphin safe sticker is used, the company may still be using techniques like FAD which will harm turtles, sharks and other protected species.

Dolphin bycatch is more of an issue in the Eastern Pacific and Central America, where dolphins get caught and killed as bycatch by Purse Seining.

You will now be able to avoid poor fishing methods and at-risk species of tuna! As with everything, quantity is also key. Reducing the amount of tuna we consume in wealthy countries and sometimes choosing a vegetarian alternative that is sustainably produced is another good way to care for the ocean. We hope this guide has been useful to you, if you would like to see more similar content in the future, feel free to chip in to help us creating guides.