NOTE: Since the time of writing, scientists have announced that for the second year in a row, a major coral bleaching event is unfolding. You can take action here.

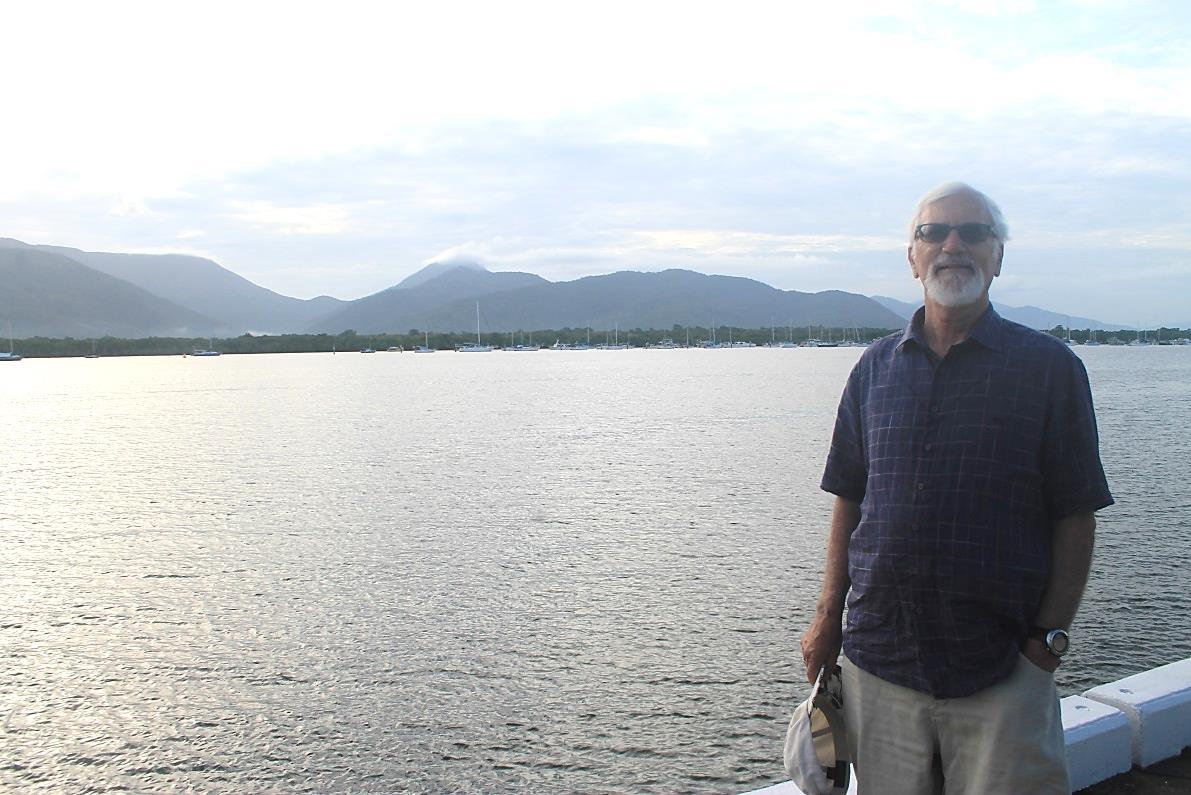

My name is Sid French. I’m a supporter of Greenpeace Australia Pacific as well as a member of the general assembly, our governing body. I’ve just recently returned from a 3 day trip to the northern Great Barrier Reef with Greenpeace CEO, David Ritter. I was there to witness the impacts of the coral bleaching event that took place almost a year ago to the day and to hear from some Reef experts about the prospects for the future.

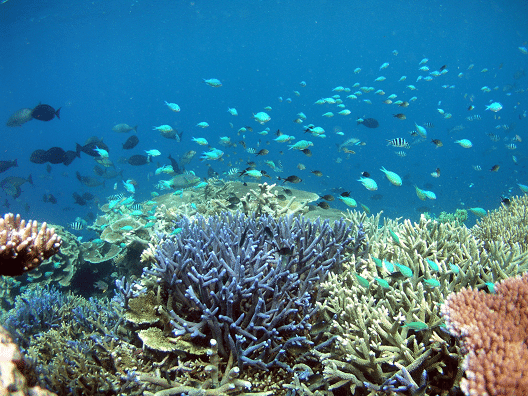

In 1981, the Great Barrier Reef was listed as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO. On their official website, UNESCO describes the Reef as one of the richest and most complex natural ecosystems on earth, and one of the most significant for biodiversity conservation.[1] According to UNESCO, the amazing diversity supports tens of thousands of marine and terrestrial species, many of which are of global conservation significance.[2]

Greenpeace has been campaigning for the protection of this natural wonder – from human-induced climate change (and cyclones, which are becoming more frequent as a result) as well as ocean acidification and shipping traffic. In 2014, UNESCO put the Australian government on probation. It became Greenpeace’s mission to make sure they didn’t forget about the Reef, and the government insisted that they had it covered. So when I plunged into the warm, tropical waters (29 degrees) off the coast of Lizard Island just last week, I was not prepared for what I saw.

Day 1

To reach Lizard Island, one must take a small 10-seater charter flight from Cairns. From the air, with a rain deluge typical to the wet season falling away behind us, the coral reefs looked as ever – perfect. It was not until a briefing with our guide and one of the directors of the Lizard Island Research Station Dr Lyle Vail, that we realised the fallacy of this apparent perfection. The coral bleaching which took place here was only visible from the air in the first few days or weeks after the event. Almost immediately, the white fluorescent appearance of bleaching (a reaction to heat stress) is covered by a beard of algae. Cue claims from certain politicians that ‘the Reef looks fine.’

Dr Vail has been living and working on the Island for 27 years and has seen this wondrous area change before his very eyes. He explains that the Reef around Lizard Island has faced a triple threat in recent years, starting with a deadly crowns of thorns starfish outbreak (possibly resulting from collectors taking their predator, the triton shell, over the last century), followed by a succession of cyclones and most recently – a mass coral bleaching event.

This bleaching was underwritten by an El Niño weather pattern, which meant months of warm water moving into the reef, and blocking weather systems, which super-heated the water until it became something of a coral soup (the southern parts of the Reef were spared the worst of this by the tail end of a cyclone that dragged colder water into the shallow seas). Unlike the tourists who flock to far north Queensland for its sun and warm tropical climate, researchers and scientists on the northern Reef pray for clouds and rain.

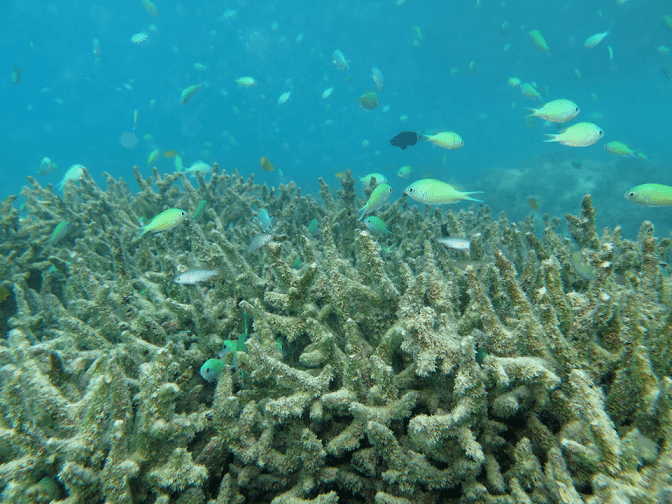

Photo: Bleached Staghorn corals on the seabed of the lagoon at Lizard Island (one surviving purple fragment can be seen at the bottom of the photo)

Day 2

The next day we set out to explore a number of dive sites to the south of Lizard Island and get a picture of the scale of the damage. The first was off the southern end of a sister island. Here, the cyclones had quite obviously ripped through a large forest of Staghorn corals and left them flattened and piled into windrows. Whatever survived was lost to the bleaching. And while a high percentage of the corals on the northern Reef are dead, there are still signs of life. Iridescent tiny fish still swim through the wreckage – and larger fish cruise in the channels. But it must be said that even the comparatively ‘better off’ parts of the reefs here still have the look of a war zone. More worrying, many of the remnant hard corals that survived the bleaching event a year ago are showing new signs of heat stress – even in a non-El Niño year, the pressure is telling. It is a sombre boat ride back to the shore.

Day 3

It’s our last day and we travel to the Outer Reef, an hour from Lizard Island, to sites I visited several years ago. The visibility here is to be marveled at, but the story for the corals is more of the same. The shallow reef is all but denuded and the detritus litters the seabed some 20 or 30 metres deep. Even within the inside walls of the Reef, which were partially sheltered from the cyclones, there is no obvious living coral. The skeletons lay strewn about as far as the eye can see. I remember my trip to this area and the famous dive site, The Cod Hole, back in 2008. There is some regrowth of soft corals covering the bones of their dead hard-boned brothers, but it is not the same. The underwater gardens are gone. A large, lone Potato Cod mopes around and there are some other fish, but not the clouds of yesteryear. It is eerily quiet. We are lucky with conditions and take the boat around to the ocean side of the Ribbon Reef, where we work our way along the rampart. Here too, the combined force of climate-boosted cyclones and an inflow of warmer water have taken their toll. The rocky terrain is largely devoid of life.

We head back towards Lizard Island with a conviction that we have witnessed the story of Lizard Island, if not the whole northern Great Barrier Reef, and it is a sad one. A final interview with Dr Vail confirms what we are all thinking; unless the human inhabitants of our world stop emitting carbon, there is little hope for the Reef. Repeated bleaching events will gradually force the fledgling corals to melt away. The researchers at the Lizard Island Research Station take solace in the few signs of regrowth since last year, but we know that the tiny coral polyps will need years to regrow and spread (and that’s without another bleaching event or cyclone).

Photo: The same area, after the bleaching in 2016 (courtesy of Dr Anne Hoggett of Lizard Island Research Station)

We are greeted back at the beach outside the research station by several turtles, grazing on the meagre sea grasses. They are a reminder that, no matter how dire the things we’ve seen are, there is still both life and wonder on the Reef. And there can be life again, but that is up to us, not them.

ACT NOW: Australia’s beautiful Great Barrier Reef is in a state of emergency. Since the time of writing, scientists have announced that for the second year in a row, a major coral bleaching event is unfolding. These events are unprecendented. Please chip in whatever you can towards our critical campaign to fight the climate crisis and protect this natural wonder here.

[1] http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/154

[2] http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/154