The Pacific region consists of 24 island states scattered across a quarter of the earth’s surface – a vast area of some 30 million square kilometres.

By description alone, the vast area should command the respect and attention of the international community.

The countries make up almost 10 percent of United Nations votes and are invaluable players in the geopolitical arena. The Pacific bolsters national security for many of the world’s biggest powers, allowing them to maintain a military presence in the region. It also hosts trade routes, provides access to deep-sea mining and floor mapping, and remains a major seafood source for the world.

In spite of this, global powers have long treated Pacific Island nations as inconsequential. Colonialism in the 1700s brought influenza and other diseases; in the mid-1800s islanders were stolen and forced to work in the plantations of larger neighbouring countries, like Australia. The Pacific was still subject to United States and French self-interests only 60 years ago, when islands were used as sites for their deadly nuclear weapons tests.

Nowadays, in a hangover from colonisation, industrialised countries continue to hold a great amount of leverage in the Pacific region while doubling as major aid donors. Australia, New Zealand, the US, China, Taiwan, Japan and Indonesia have vested interests throughout the Pacific in a range of sectors, including fisheries, infrastructure development and telecommunications. Global superpowers have evolved and adopted a gift-giving and resource-taking role throughout the region.

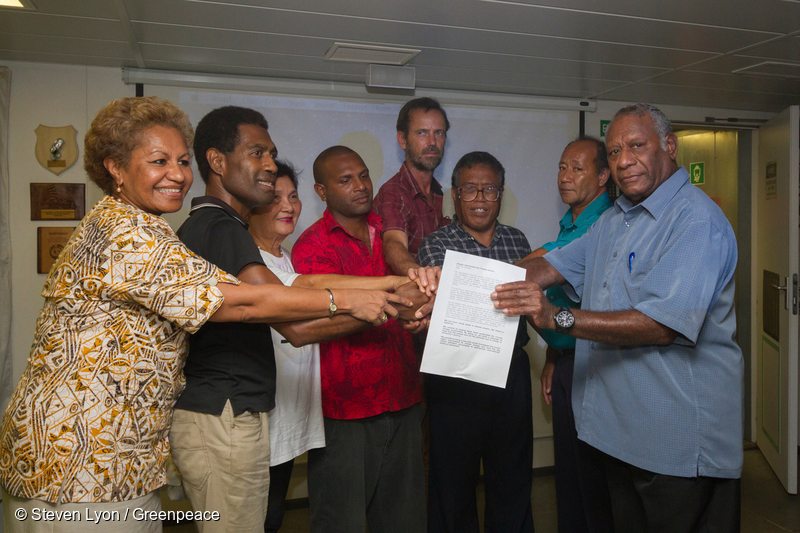

However, the era of the Pacific countries being passive recipients is quickly drawing to a close. Pacific leaders have begun to subtly shift this deeply embedded political dynamic to restructure their foreign relationships. They are creating more political power for themselves, and regaining control over their precious natural resources.

In 2007, Pacific leaders signed a declaration for region-wide management of their fisheries resources. This increased financial returns from the industry, while also strengthening conservation measures. Decades prior to that change, a vast majority of the fisheries business, including processing, took place in Asia, US and Europe – locking the Pacific Islands out of the profits from their own resources.

This declaration sent a message to foreign governments and companies that the Pacific would no longer politely stand by while their fisheries were exploited and wiped out. As a result, the Pacific tuna fisheries industry is now more regionally driven, and in the hands of Pacific governments. Furthermore, the collapse in January 2016 of a decades-old regional treaty with the US on tuna fishing rights has allowed Pacific governments more control over their tuna industry.

Pacific Island nations have also begun to push back against the control that Australia and New Zealand wield over the Pacific Island Forum, which for decades has been the main intergovernmental platform for the region. At the 2015 PIF Leaders Meeting in Port Moresby, Kiribati’s then President Anote Tong publicly criticised Australia and New Zealand, saying that development aid could no longer be used as a puppet string for the Pacific while survival from climate change threats were not being addressed.

“What we are talking about is survival, it’s not about economic development… it’s not politics, its survival. I think they need to come to the party, if they really are our friends then they should be looking after our future as well.”- President Anote Tong of Kiribati, 2015.

In 2013, Pacific nations – except Australia and New Zealand – met for the first time as the Pacific Island Development Forum (PIDF) to talk about sustainable development without international influence.

The PIDF last year produced the stand-out ‘Suva Declaration’, a document articulating the authentic concerns of Pacific Island states over climate change ahead of the United Nations Paris climate talks. It called for a more ambitious global emissions reduction target than a similar document from the Pacific Island Forum, reflecting the seriousness of the climate crisis for low-lying Pacific nations.

Before Paris last year, Fiji’s Prime Minister, Voreqe Bainimarama, reminded Pacific delegates to the climate talks to press global superpowers on their climate responsibilities, and to do so with a refreshed and more powerful Pacific approach.

“The industrialised nations are putting the welfare of the entire planet at risk so that their economic growth is assured and their citizens can continue to enjoy lives of comparative ease. All at the expense of those of us in low lying areas of the Pacific … I won’t be going to Paris wearing the usual friendly, compliant Pacific smile. In fact, I won’t be going to Paris in a Pacific frame of mind at all. Standing shoulder to shoulder with the other island leaders, I will sternly remind the industrialised nations of their obligations and press as hard as I can for the adoption of the recent Suva Declaration.” – Prime Minister Voreqe Bainimarama of Fiji, 2015.

Furthermore, this month, we saw long-overdue muscle-flexing from the Republic of the Marshall Islands (RMI), one of the tiniest countries in Micronesia. In a display of courage, RMI is currently taking on some of the world’s biggest nuclear powers – Britain, India, and Pakistan – in an unprecedented legal case at the International Court of Justice in The Hague. Generations of Marshallese, past and present, have suffered the severe after-effects of dozens of nuclear tests conducted in 1940s and 1950. RMI are now trying to hold the world’s nuclear weapons states accountable for failing to act on nuclear disarmament.

As the rise of Pacific power strengthens region-wide, a class action suit by Pacific Islanders against fossil fuel corporations is set to be filed in Fiji towards the end of 2016. Led by civil society, the case intends to address human rights violations occurring across the Pacific due to the climate crisis. It will seek to prohibit the further extraction of fossil fuels by the ‘Carbon Majors’ – those corporations responsible for causing and perpetuating the ongoing destruction of earth.

Pacific nations are at the forefront of many global challenges, the most urgent being climate change. The Pacific has united and ignited change in the past, altering international regulations around nuclear dumping, radioactive waste, laws of the sea and driftnet fishing. It can be done again.

Pacific Islanders do not have to relinquish their beaches to fossil fuel companies, their marine life to offshore political deals and their human rights to corrupt corporations. The Pacific has a say in the fate of its people and it is finally speaking up.