30 years ago, the first big international environmental catastrophe in my memory occurred. It’s one that’s stuck with me ever since for its visceral images of struggling seabirds blinking beneath thick coats of brown-black oil.

March 24 2019 marks three decades since the Exxon Valdez oil tanker ran aground at Prince William Sound, Alaska. It spewed somewhere between two and five hundred thousand barrels of oil into the environment right at the peak of spring when the animals, like otters and sea-ducks, were at their most active.

This image, taken in Prince William Sound is July 2018 by D. Janka, is a reminder that oil spill cleanup is a myth and the damage from a spill can be permanent. Only 7% of the Exxon Valdez oil is estimated to have been recovered, in the deepwater horizon disaster it’s estimated only 4% was recovered.

The response from Exxon (who we know in Australia as Mobil or Esso) involved over 11,000 cleanup workers, 1,400 boats, and 100 aircraft. In an attempt to ‘remove’ the oil they sprayed hot and cold water and chemical dispersants to loosen it up and spread it through the water column and across the sands and rocky shorelines. They used brooms, shovels, and machinery to push, scrape, and scoop away the oil-sodden soil and pebbles and leaf matter of the coastal forests. They tried booms to contain and then attempt to skim the oil off the water’s surface where it had collected. They tried for three whole years.

Of course it was ineffective – oil had penetrated up to 2 metres into the surface of the coastlines. Storms and ocean currents blew the surface oil hundreds of kilometres away to damage new beaches, bays, and cliff faces. Oil just isn’t that easy to clean up. In all, the oil covered 26,000 square kilometres of Alaskan ocean and 2,100km of coast – that’s the equivalent of roughly from Torquay on the Great Ocean Road all the way to South Australia. It’s estimated that at best, only 7% of the oil was ever removed.

Professor Rick Steiner, a marine ecologist and former Alaskan fisherman who witnessed the disaster first-hand, visited Australia last year to warn us about the dangers of drilling for oil in the Great Australian Bight. He brought with him images that would send a chill down the spine of anyone who’s ever strolled along a beach or spent a day in the surf. The oil from the Exxon Valdez spill in Alaska is still there in many places – three whole decades later.

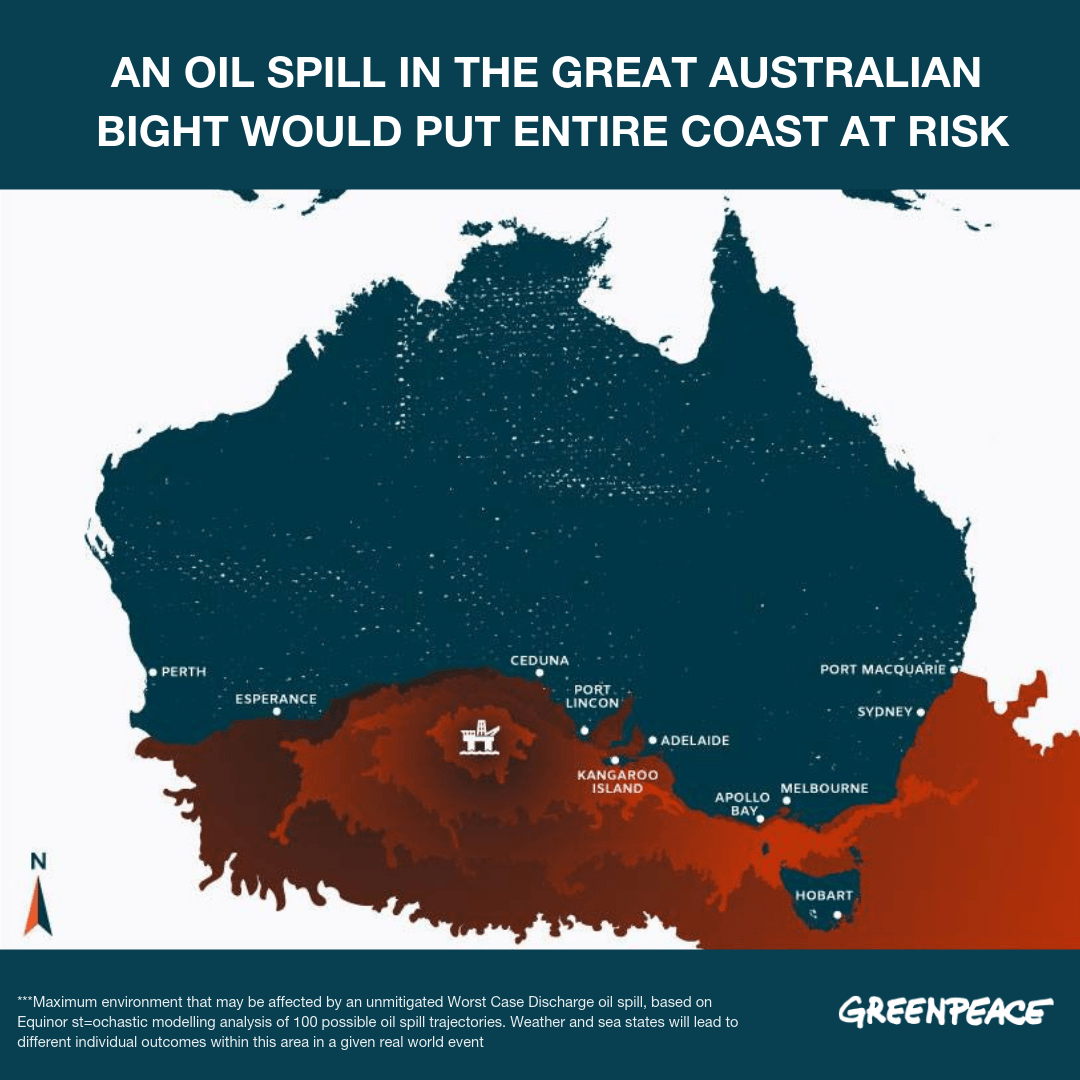

Equinor’s own modelling shows that an oil spill in the Bight could hit the coastline anywhere from WA to northern NSW

It’s a conspicuous reminder of what could be in store for the Great Australian Bight if oil giant Equinor’s plans to drill for oil go ahead.

The Bight includes some of the most remote and inaccessible coastline in Australia. If the worst case oil spill scenario modelled by Equinor did occur, it would cover thousands of kilometres of coastline. The oil companies admit that they won’t ever be able to clean up all the oil – that some areas will have to be left to nature. In fact, the amount they can clean up has been described as ‘environmentally irrelevant’.

The toll of the Exxon Valdez disaster remains hard to quantify. It’s unknown how many animals died as a result of the Exxon Valdez spill but it numbers in the hundreds of thousands. We know that half of the species are still not recovering – including its population of killer whales. We know that Inuit cultural practices and food harvesting was damaged. We know that fishermen lost their livelihoods which means the mechanics who fix their boats would have too, and so on.

What we do know is that the only way to guarantee no one goes through this again is to end the age of oil.

Email Australia’s Environment Minister now and call on her to put a stop to oil drilling in the Bight.