Blogpost by Joss Garman, Greenpeace UK

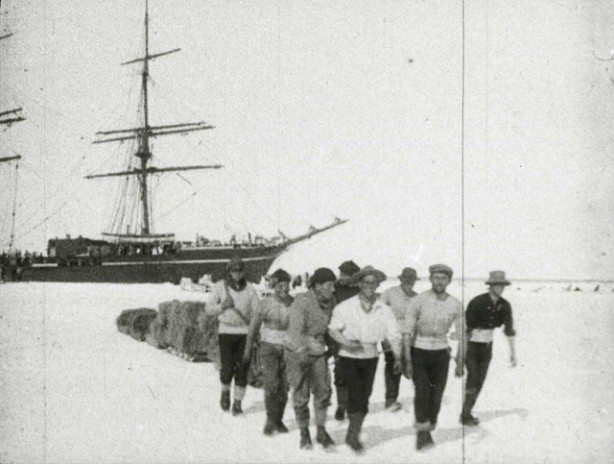

Group of men, in the background the steam Yacht 'Terra Nova'. Date: c.1911 © Herbert PontingSource: The National Archives UK on flickr.

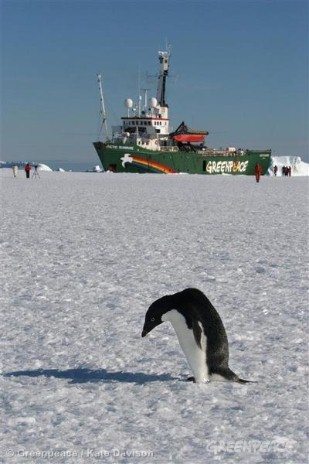

Staring out at the bright, open, broken plains of Arctic sea ice back in September, more than once I was struck by the thought of the early explorers who first trekked across similar icescapes at both of the frozen ends of the planet. My first time stepping down onto the floating Arctic ice was exciting enough; hard to comprehend what it was like for those who were pushing the boundaries of where humans had previously explored.

But beautiful as it may be, seemingly endless expanses of ice and water are also seriously inhospitable – underlined in those famous words of the British exploring legend Captain Robert Falcon Scott.

He was referring to his companions – Edward Wilson, Henry Bowers, Lawrence Oates and Edgar Evans – who walked with him the last march to the South Pole and like him never made it back alive. Their bodies, together with Scott’s diaries, were found later, in November 1912.

Robert Falcon Scott's Pole party of his ill-fated expedition, from left to right at the Pole: Oates (standing), Bowers (sitting), Scott (standing in front of Union Jack flag on pole), Wilson (sitting), Evans (standing). Bowers took this photograph, using a piece of string to operate the camera shutter. Date 17/01/1912 © Lieutenant Henry Bowers/SPRI

Whilst of course it’s true that on his voyage to the South Pole a century ago – “the worst journey in the world”- Captain Scott and his team never would have had to deal with the prospect of polar bears popping up from behind ice floes – remember, there are no bears in Antarctica – they did have to battle with even colder temperatures than anything experienced in the High North. They had spent weeks journeying in an environment regularly more than 37 degrees centigrade below freezing. One evening of our Arctic trip last year, in the comfort of the mess of the Arctic Sunrise, we spent a couple of hours discussing just quite how remarkable those adventures must have been. Our expedition leader, Frida, who is much more informed about the early explorers than I am, enthused contagiously about her fellow Scandinavian Roald Amundsen who ultimately won the race to the South Pole. As she describes in the blog post remembering the anniversary of his achievement:

“Amundsen was fascinated by the Polar Regions since his early years. Back then he was sleeping with the windows open, enduring the cold Norwegian nights to strengthen his body and ready himself to explore those regions. The dreams of the boy became the epic adventures of the man who navigated through the Northwest Passage (1903-1906), reached the South Pole 100 years ago, and flew over the North Pole on the airship Norge in 1926.”

Whilst Amundsen may have been the first person to undisputedly reach both North and South Poles, Captain Scott discovered 400 new animal species in Antarctica, and made monumental scientific findings, as well as breaking ground in geographicalunderstanding – as Sir David Attenborough recently recalled for the BBC.

Everybody I know who has ventured into the Polar Regions has an infectious passion for their wild magnificence, beauty, biodiversity, and consequently their protection. So it surely cannot be any coincidence that Captain’s Robert’s son – Sir Peter Scott – became a founding father of the modern environment movement, one of those who established WWF and the IUCN, the International Union for Conservation of Nature. Nor surely, with Sir Robert as his father, can it be any surprise that Sir Peter’sdriving passion should have been preservation of Antarctica from human exploitation.

But now Antarctica, like the Arctic, is undergoing changes with consequences that will be felt around the world. The National Snow and Ice Data Centre, one of the leading Polar research institutes in the world, says “[…] that Antarctic sea ice plays an important role in climate, helping to protect the Antarctic Ice Sheet from waves, warmer surface water, and warmer air that can destabilize Antarctica’s ice shelves and help speed the flow of continental ice into the ocean. And in some regions, Antarctic sea ice is not as stable as it used to be.” Meanwhile at the other end of the planet, Arctic sea ice has shrunk by about 10% per decade since 1979 – about 72,000 square kilometres (28,000 square miles) per year. Given the role of the Arctic sea ice in keeping the global climate stable, this is hugely significant for millions of people around the world.

Keeping in mind these dramatic changes at the Poles, and remembering their significance for the rest of the world, Captain Scott could have had no inkling of the wider resonance of his final diary entry. Now his last known words – “For God’s sake look after our people” – could offer us a new rallying cry as we campaign to protect the fragile balance of the Earth.

“Had we lived I should have had a tale to tell of the hardihood, endurance and courage of my companions which would have stirred the heart of every Englishman. These rough notes and our dead bodies must tell the tale.”