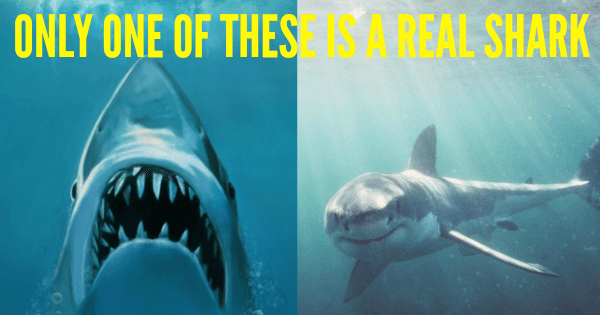

I’ve never watched Jaws. Somehow, though, any mention of the movie thrusts an image to the forefront of my mind: a gargantuan beast rising from cerulean depths, mindlessly charging towards vulnerable prey; rows of jagged teeth braced, black irises stoic as it prepares to tear apart human limbs and chew asininely on a once living, breathing, sentient being.

But of course there is much wrong with that picture. White sharks do not chew their prey, have lifeless black eyes, or want to eat humans. They are intelligent, curious, sensitive animals.

Why are we scared of sharks?

Where does a seemingly visceral fear of these sanguine sea-dwellers come from? It would be amiss to simply point the finger at Spielberg. We, like the author of Jaws, must admit – our fear is built on ignorance. And seeing as ancients sharks existed over 400 million years before we turned up, it’s not surprising that we still have much to learn.

Sharks: evolution’s success story

What we do know is pretty incredible. Maybe it’s no wonder we’re scared of a great white’s teeth when they’re the result of millions of years of evolutionary finessing.

White sharks are streamlined swimming machines with highly-developed senses. It’s this awe-inspiring talent that make them apex-predators – and makes their disappearance from an ecosystem even more dangerous.

Ancient sharks existed 400 million years before humans. Respect your elders.

Sharks are friends, not food

Which is why there are dedicated teams of conservationists and scientists working to understand and protect these beauties. After participating in a shark tagging research project two-decades in the making, Australian scientist Barry Bruce noted that beachgoers have been hanging out with sharks much more than previously thought:

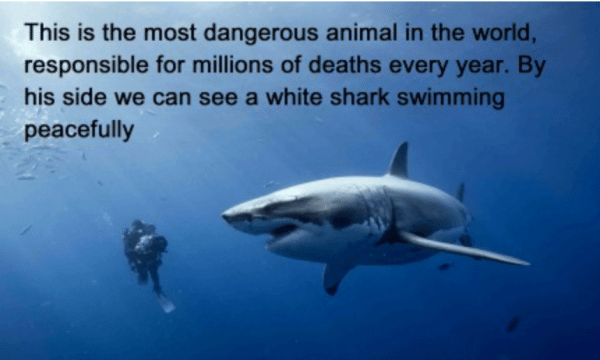

“One thing that is becoming clearer is that people and sharks (including white sharks) share the same space more frequently than we previously realised. This is not because numbers of sharks have suddenly increased; it is because we are getting better information on shark movements.

The more we look the more we see. For example we know of some areas in eastern Australia where white sharks and people commonly swim at the same beach at the same time – yet there has never been an attack at these beaches – in fact in most cases you would not know they were there.”

What can we take from this confirmation that our oceans are well and truly shark-infested? Perhaps we can start by seeing sharks in our waters as a sign of a healthy ecosystem rather than an infestation problem – made almost miraculous amongst the 100 million shark bodies humans haul to fish heaven every year.

Dr Bruce’s research also vindicates one of the most compelling shark preservation arguments – that we’re much less likely to die of a shark attack than we might think.

Photo via Imgur

Tell Mike Baird to save sharks

Alarmists in the media are running a scare campaign to pressure NSW Premier Mike Baird to kill sharks. They want NSW to put up more deadly shark nets or even ruthlessly cull sharks, like Colin Barnett tried in Western Australia in 2014.