We usually refer to them as Pacific Island nations, but calling places like Kiribati ocean nations is more accurate. The people of Kiribati are not just surrounded by oceans – they depend on healthy oceans for survival.

Kiribati forms one of the biggest exclusive economic zones (EEZ) in the world and boasts one of the most productive tuna fisheries. Over 250,000 tonnes of tuna is caught here each year making it the second largest provider of this supermarket staple in the world, after Papua New Guinea. Kiribati is a nation of sailors and fishermen – yet almost all of that tuna is taken by foreign vessels.

Fish is essential to Kiribati for income and employment – but more crucially for this developing state, beset by poverty and the impacts of climate change, fish is essential for food security. Seafood makes up almost one-third of the average Kiribati diet and provides most of the protein. As coral reef ecosystems become less healthy, that diet is increasingly made up of pelagic fish such as tuna.

The way the locals fish has barely changed in decades. For years, small crews of three have gone out daily in wooden boats to supply tuna to local towns and villages. They try to stay within sight of land if possible to avoiding becoming lost at sea, which occasionally, tragically, they do. There is no GPS, no radar, no back up engine, and no radio. There is no ice to bring their catch back in a condition for export.

Kiribati is home to both some of the smallest and largest fishing boats in the world.

| – | Local fishing boat | Spanish monster boats |

| Length of boat | 5-7m | Up to 115m |

| Daily catch | Up to 50 tuna a day | Up to 200 tonnes of tuna a day |

| Annual catch | In 2008, the entire artisanal tuna fishery of Kiribati caught 12,500 tonnes of tuna | A monster boat such as the Spanish Albatun Tres can catch up to 2000 tonnes of tuna in a single fishing trip. |

| Fishing method | Trolling with a hand-line (one line, one hook) | Purse-seine nets with Fish Aggregating Devices (FADs) |

| Bycatch | None | Juvenile tuna, sharks, rays and even turtles, especially when FADs are used. |

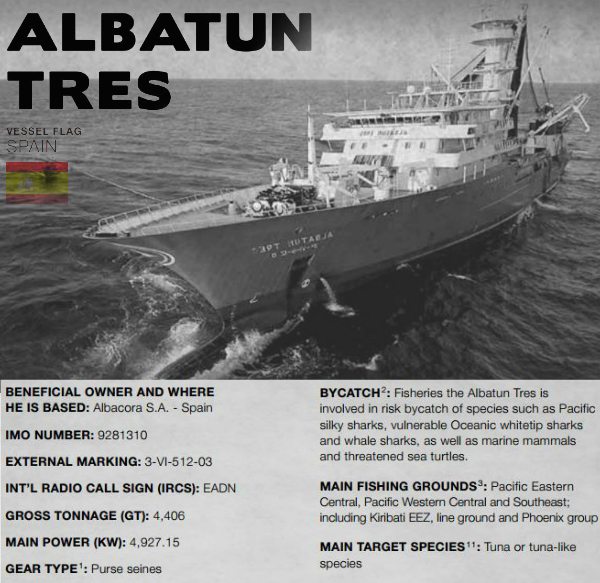

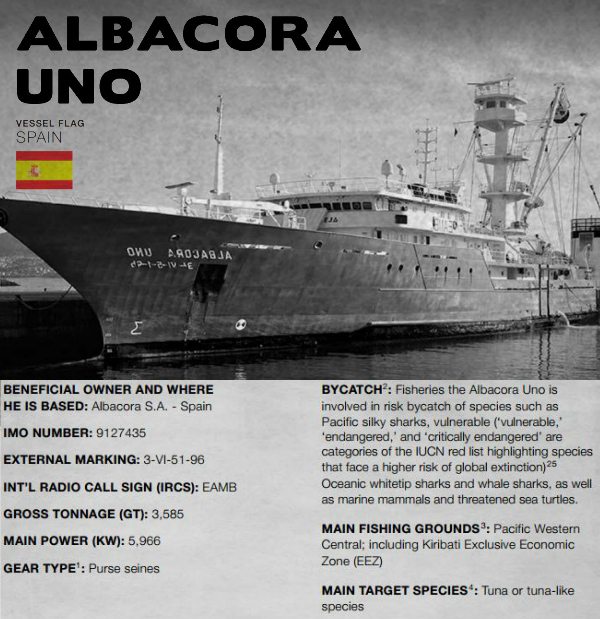

Profiling the monsters: Albatun Tres and Albacora Uno

The two biggest – Albatun Tres and Albacora Uno, owned by the biggest tuna fishing company in Europe, Albacora – can catch more in three combined fishing trips than the entire local fleet catches in a year.The tiny scale of local fishing is made stark by the sight of the giant foreign purse seine vessels ringing the lagoon of the main island, Tarawa. Casting a shadow over the others are the Spanish monster boats – the biggest tuna fishing vessels in the world.

Their technological capability is staggering in contrast to that owned by Kiribati fishermen, who rely on reading nature using skills passed down from father to son. The monster boats are marvels of industrial fishing and globalisation.

They are equipped with satellites that detect plankton and ocean currents, bird radar to spot schools of fish, and most destructively, fish aggregating devices (FADs) equipped with sonar and homing beacons – the latter attract vast schools of fish and other marine life, including tuna, and tell the monster boats when the biomass of ocean life is ready to be collected. What won’t sell on the international tuna market is thrown back dead.

Tuna is big business, but to visit Kiribati you wouldn’t know it.

Although more than USD $2 billion worth of tuna was caught in Kiribati waters in the last two years, only a fraction of this value was returned to Kiribati. Last year the gross domestic product of Kiribati was USD $169 million for a nation of over 100,000.

The combined revenues of Albacora and its subsidiaries was over €475 million in 2012. Yet, it has received millions in European taxpayer subsidies to build its monster boats and send them to Kiribati.

The deal the EU signed with Kiribati that allows Albacora to fish these productive waters gives little back to the people who have a right to this potentially life-changing resource. More importantly, it undermines progressive regional attempts by Pacific Island countries to jointly manage their tuna resource for the future and to earn an adequate return.

Greenpeace is for fair, sustainable fishing, in the Pacific and elsewhere. Our ‘monster boats’ report highlights the worst excesses of the European fleet that have contributed to emptying fish stocks and robbing small-scale fishermen of jobs.

Last year, Greenpeace released a roadmap for transforming Pacific tuna fisheries so Pacific states get a fair return and the local fishing economy grows.

Until the EU can pay a fair price, it should take its monster boats and go.