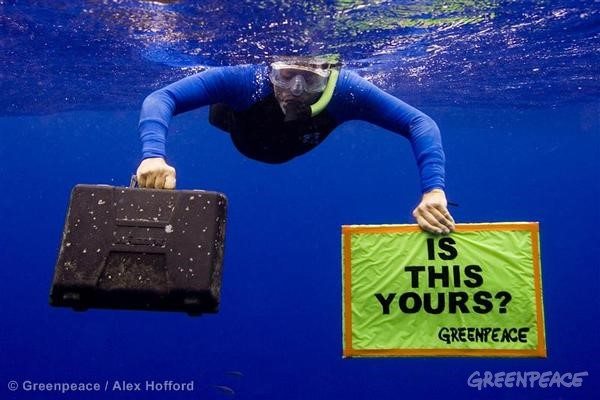

You could save a turtle’s life by using less plastic and making sure your garbage is properly managed. In the North Pacific is an area the size of Turkey of floating plastic rubbish. It is rubbish from the land that is polluting our oceans, choking and trapping millions of fish and animals. We can keep plastic trash out of our ocean and save ocean life.

You could save a turtle’s life by using less plastic and making sure your garbage is properly managed. In the North Pacific is an area the size of Turkey of floating plastic rubbish. It is rubbish from the land that is polluting our oceans, choking and trapping millions of fish and animals. We can keep plastic trash out of our ocean and save ocean life.

Take a walk along almost any beach anywhere in the world and washed ashore will almost certainly be either plastic bags and bottles, or containers. Perhaps plastic drums or expanded polystyrene packing. All too often there are polyurethane foam pieces, pieces of polypropylene fishing net and discarded lengths of rope. Together with traffic cones, disposable lighters, tyres and even toothbrushes, this plastic trash has been casually thrown away on land or at sea and has been carried ashore by wind and tide.

One of the things that make plastic so heavily used domestically and commercially – its durability – also makes it a major problem for our oceans, and will continue to do so for generations. Around 100 million tonnes of plastic are produced each year, of which about 10 million tonnes ends in the sea. About 80% of it comes from land.

The larger items are the visible signs of a much bigger problem. At sea and on shore under the influence of sunlight, wave action and mechanical abrasion these larger items slowly break up into smaller pieces. Plastic doesn’t break down like natural materials – it doesn’t go away, it just goes from being a floating bottle to tiny plastic particles that are easily eaten by fish and other marine species or simply spread even further afield. A single one-litre bottle could break down into enough small fragments to put one on every mile of beach in the entire world.

Small plastic pellets aren’t just the result of natural erosion. Cargo ships are increasingly carrying packing cases using small plastic pellets as stuffing and these are liberally dispersed across the oceans when drum-loads or even container loads are lost at sea. The pellets are frequently found during beach clean-ups, but also at sea in areas where winds and currents are weak.

The “Trash Vortex”

The North Pacific sub-tropical gyre covers a large area of the Pacific, in which the water circulates clockwise in a slow spiral. Winds are light and the currents tend to push any floating material into the low energy centre of the gyre. There are few islands on which some of the floating material beaches. So most of it stays there in the gyre, in astounding quantities – estimated at six kilos of plastic for every kilo of plankton. The “Trash Vortex”, also known as the “Eastern Garbage Patch”, is an area equivalent in size to Texas, or Turkey, or Afghanistan, that slowly rotates our rubbish in a never-ending rotation.

Some of the larger items are consumed by seabirds and other animals, which mistake them for prey. Many seabirds and their chicks have been found dead, their stomachs filled with bottle tops, lighters and balloons.

A turtle found dead in Hawaii had over a thousand pieces of plastic in its stomach and intestines. It has been estimated that over a million seabirds and one hundred thousand marine mammals and sea turtles are killed each year by either eating or getting tangled in six-pack plastic can holders and discarded netting, fishing lines and other bits of discarded plastic.

Chemical sponge

Plastics can also act as a sort of “chemical sponge”, concentrating many of the most damaging of the pollutants found in the world’s oceans: the persistent organic pollutants (POPs). So any animal eating these pieces of plastic debris will also be taking in highly toxic pollutants.

Ocean hitchhikers

Bits of floating plastic can also provide easy transport for plants and animals to move into oceans beyond their normal habitat – these alien species often causing major problems by disturbing the natural balance of the ecosystem.

The North Pacific gyre is one of five major ocean gyres. The Sargasso Sea is a well-known slow circulation area in the Atlantic, and research there has also demonstrated high concentrations of plastic particles present in the water – it’s own Trash Vortex. The Sargasso Sea is home to a rich selection of marine life including fish, turtles and whales and is the breeding ground of the European eel. The Sargasso Sea one of the areas identified by Greenpeace that should be protected as an Ocean Sanctuary.

Governments around the world are now negotiating a Global Plastics Treaty – an agreement that could solve the planetary crisis brought by runaway plastic production. Let’s end the age of plastic – sign the petition for a strong Global Plastics Treaty now.

Sign petition