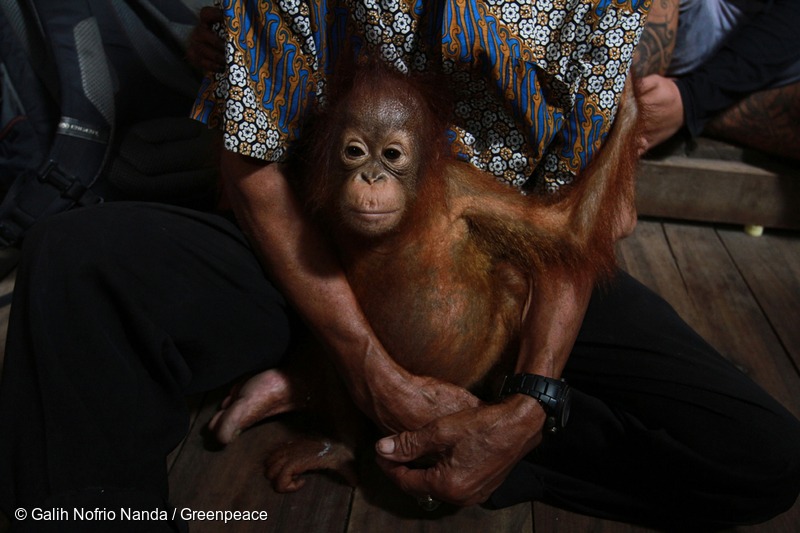

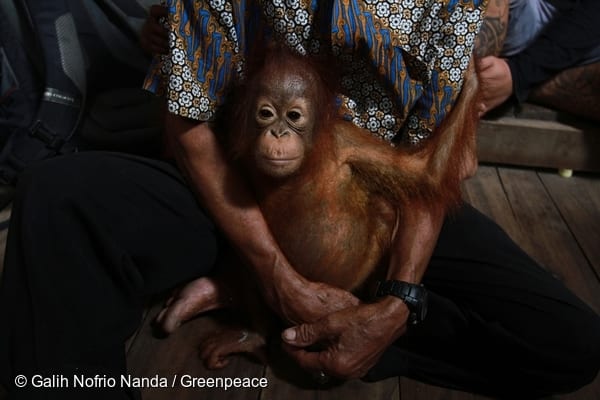

For half an hour Otan wouldn’t let go. Only eight months old, he already had a vice-like grip, his nails digging so deep they left half-moon imprints in the skin of his carer. If there were trees, Otan would be swinging freely from branch to branch, his strong grip lifting him in high arcs through the forest canopy. But there were no more trees left for Otan.

The baby orangutan was rescued from forest fires while drinking water from a river in an oil palm plantation near the village of Linga, Sungai Ambawang Kubu Raya.|A rescued 7 month old orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus) named Otan under the custody of the Conservation and Natural Resources (BKSDA), an orangutan rehabilitation centre in Sungai Ambawang Kubu Raya, West Kalimantan.

The baby orangutan was rescued from forest fires while drinking water from a river in an oil palm plantation near the village of Linga, Sungai Ambawang Kubu Raya.|A rescued 7 month old orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus) named Otan under the custody of the Conservation and Natural Resources (BKSDA), an orangutan rehabilitation centre in Sungai Ambawang Kubu Raya, West Kalimantan.

The baby orangutan was rescued from forest fires while drinking water from a river in an oil palm plantation near the village of Linga, Sungai Ambawang Kubu Raya.|A rescued 7 month old orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus) named Otan under the custody of the Conservation and Natural Resources (BKSDA), an orangutan rehabilitation centre in Sungai Ambawang Kubu Raya, West Kalimantan.

The baby orangutan was rescued from forest fires while drinking water from a river in an oil palm plantation near the village of Linga, Sungai Ambawang Kubu Raya.|Residents rescue a 7 month old orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus) from forest fires, while he was drinking water from the river in an oil palm plantation near the village of Linga, Sungai Ambawang Kubu Raya, West Kalimantan.

The orangutan is now under the custody of the Conservation and Natural Resources (BKSDA).|Residents rescue a 7 month old orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus) from forest fires, while he was drinking water from the river in an oil palm plantation near the village of Linga, Sungai Ambawang Kubu Raya, West Kalimantan.

The orangutan is now under the custody of the Conservation and Natural Resources (BKSDA)., Ayu memasukkan Otan, individu orangutan (Pongo Pygmaeus) berumur sekitar 7 bulan, kedalam kandang untuk di rescue dari Desa Lingga, Kecamatan Sungai Ambawang Kabupaten Kubu Raya, Kalimantan Barat, Jumat (18/9/2015). Warga menemukan Otan sedang meminum air sungai di kawasan perkebunan sawit, saat diberi makan Otan tak mau juga pergi dan akhirnya dibawa warga. Otan akhinya dievakuasi Balai Konservasi Dan Sumber Daya Alam (BKSDA) Kalbar dan akan direhabilitasi, Ayu memasukkan Otan, individu orangutan (Pongo Pygmaeus) berumur sekitar 7 bulan, kedalam kandang untuk di rescue dari Desa Lingga, Kecamatan Sungai Ambawang Kabupaten Kubu Raya, Kalimantan Barat, Jumat (18/9/2015). Warga menemukan Otan sedang meminum air sungai di kawasan perkebunan sawit, saat diberi makan Otan tak mau juga pergi dan akhirnya dibawa warga. Otan akhinya dievakuasi Balai Konservasi Dan Sumber Daya Alam (BKSDA) Kalbar dan akan direhabilitasi|Residents rescue a 7 month old orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus) from forest fires, while he was drinking water from the river in an oil palm plantation near the village of Linga, Sungai Ambawang Kubu Raya, West Kalimantan.

The orangutan is now under the custody of the Conservation and Natural Resources (BKSDA).|Residents rescue a 7 month old orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus) from forest fires, while he was drinking water from the river in an oil palm plantation near the village of Linga, Sungai Ambawang Kubu Raya, West Kalimantan.

The orangutan is now under the custody of the Conservation and Natural Resources (BKSDA).|Residents rescue a 7 month old orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus) from forest fires, while he was drinking water from the river in an oil palm plantation near the village of Linga, Sungai Ambawang Kubu Raya, West Kalimantan.

The orangutan is now under the custody of the Conservation and Natural Resources (BKSDA).

8-month old Otan who lost his mother and home due to deforestation.

I was with a Greenpeace team in fire-ravaged West Kalimantan last month, when I heard some news from Linga Village, about 30 minutes by road from the capital, Pontianak in which villagers were nurturing a wild orangutan. Otan’s home had been razed to make way for an oil plantation. Only small patches of forest were left, but in time those areas would be razed too.

Workers at a palm oil plantation had first spotted the baby primate peeking at their camp in August. Their forest habitat dwindling, hunger-struck orangutans were being forced towards villages in search of food. At first, Otan was too scared to approach the workers’ camp, but eventually he came forward, and the workers fed him rice and water. After eating he would return to the forest, but each morning without fail he would always reappear. This continued for weeks.

Otan being fed milk.

“It’s very rare to see a baby orangutan alone,” said local villager, Ivan Nurisaputra. “Usually, they’re accompanied by their mother until a certain age.”

Ivan confirmed that the nearby peat forests were the orangutans’ home.

“We’ve seen orangutan nests in the peatlands, but they’re empty. Otan can’t find his mother. There’s no forest left,” said Ivan looking forlorn.

Ivan and his wife Ayu assumed responsibility for the hungry and listless Otan and nursed him for about a week, but despite their best intentions, they were at a loss trying to properly care for him.

22-year old Ayu Nurisaputra holds 8-month old Otan.

“We would give him three or four glasses of milk a day. When he was hungry we’d give him rice with stir-fried vegetables. But sometimes he’d fall sick with diarrhoea and fever,” said Ivan. “We were afraid he would die, so that’s why we decided to give him up.”

Ayu and her father-in-law play with baby Otan.

They contacted the National Conservation Agency (NCA) of West Kalimantan, whose staff are trained in looking after these endangered creatures. But when the officials came to take Otan, he clung tight to Ayu. He’d lost his mother, his home and now he was going to lose everything again.

Ayu carries baby Otan to a cage so he can be taken to an orangutan sanctuary.

Ayu helps an officer from the NCA place Otan into the cage…

… but Otan is scared and reluctant to go in.

After 30 mins Otan is placed into the cage. Ayu holds his hand.

For half an hour Otan wouldn’t let go.

The Guardian estimates that a third of the world’s remaining orangutans are threatened by Indonesia’s fires. During a boat ride down the Rungai River in Central Kalimantan, passing through an orangutan habitat near the Nyaru Menteng sanctuary, I saw first-hand how sick the animals had become. Just like us, tiny particles of toxic smoke penetrate deep into their lungs, causing them to cough and suffer flu-like symptoms. What’s worse, we recently discovered that an area once covered by peat forest just five minutes away from the sanctuary had been completely burnt, and freshly re-planted with palm oil saplings.

It seems like there is no end to this senseless destruction. For over a decade, Greenpeace has been exposing the rampant deforestation of Indonesia’s forests and peatlands. In that time, an area of forest the size of Germany has been destroyed, led by the rapid expansion of the pulp and palm oil sectors.

A few days ago, an image of an emaciated mother orangutan and her daughter went viral. In the mother’s eyes you can see her desperation and trauma as her child tries to bury herself into her bosom. I feel that same pain when I think of Otan and what he must have gone through. How many more forests need to be razed and burned just to make products we buy? How many more orangutans like Otan must lose their mothers and homes because of greedy palm oil companies?

Half a million people have been sickened by toxic smoke — we need government action and company transparency to stop the fires for good.

**Update: Otan is now safe and sound in an orangutan sanctuary in Ketapang Regency, West Kalimantan.

Will you take action and save the homes of endangered wildlife like Otan? Get involved here to hold government and companies accountable for this destruction, or donate now to help fund this critical campaign.

Zamzami is a Media Campaigner with Greenpeace Southeast Asia, based in Pekanbaru, Indonesia.